BWMSTR Label - New sources of encounters in the city

Research

New sources of encounters in the city was selected by Vlaams Bouwmeester, the Flemish Government architect, for the BWMSTR label, a scheme that supports innovative ideas aligned with current policy with grants and endorsement.

With the threat of a global freshwater shortage in the perhaps near future, one of the challenges for today’s cities is to be smarter about how they use, supply, and provide water as a valuable urban element. More urgently, when increasing numbers of heat waves are forcing urban dwellers to leave the city to cool down, the message is clear that urban planning can no longer ignore, let alone deny, the importance of considering more carefully the role of water in the future city.

Furthermore, throughout history, water has always functioned as a connecting factor, bringing people together and offering an immediate social dimension. Which in turn leads to another urgency of the contemporary urban context, in which ‘large-scaliness’ and the consequent anonymisation often lead to loneliness and alienation. Two components that therefore became the spearheads of this study and were captured in the research question: ‘How can we reintroduce meeting places around water into the public urban space where people like to come together and become more aware of the impending water shortage?’

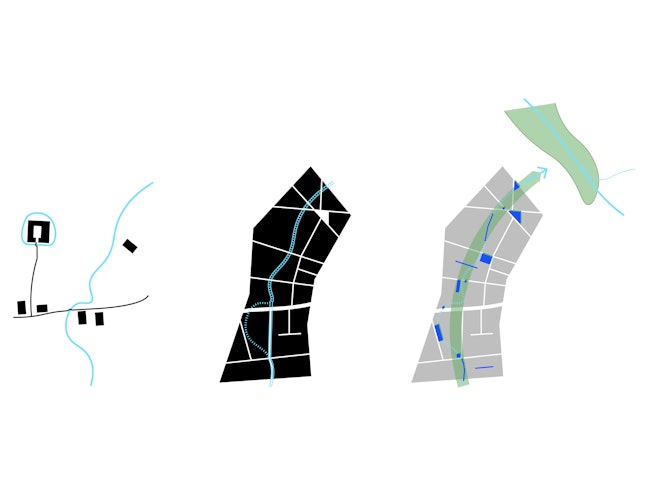

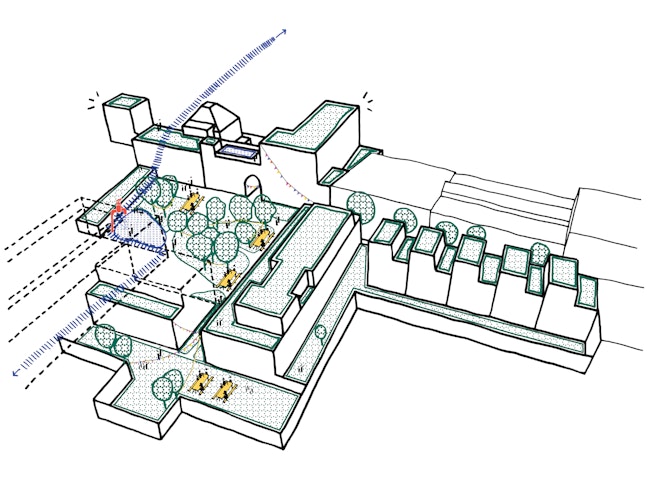

It sufficed to look at B’s own immediate surroundings, with Borgerhout being one of the most paved areas in the city of Antwerp. Motivated by the statement ‘Where water once flowed, it will find its way again’ by professor and hydrologist Boud Verbeiren, a search began to rediscover the water in this neighbourhood. A vanished brook became the starting point for a strategic plan, in which different places along the route of this erased waterway were selected and acupuncturally pierced, so that water was reintroduced, with both a private, a semi-private, a public and a semi-public status.

In turn, these different places are linked to four water figures. For example, ‘the well’ represents a private place where habitants can fetch water and chat, while the ‘water island’ relates to the residents of an entire block. The ‘pond’ is a semi-public place that invites residents to play, relax and meet, and the ‘water square’ is a visible public space that is a direct and vital part of the city layout. All together, they link up to form a new urban river and provide a blue-green trajectory, functioning as signposts through the dense urban fabric and drawing attention to water scarcity.

1 - Dodoensstraat

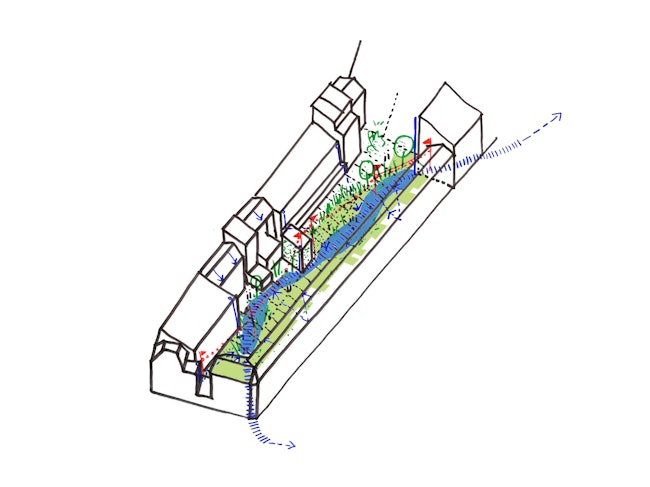

In the first case study, the course of the old brook runs along the private area of the residential nineteenth-century building block in Dodoensstraat - the street named after the 15th-century physician, herbalist and botanist Rembert Dodoens.

In the same areas where gardener Van Geert maintained stretched gardens for a long time, we now experience water damage where buildings were built too close to the watercourse. Today, a few rear buildings still bear witness to water damage. Nature needs open space, while man built a sequence of back gardens for the sake of privacy.

A demarcated area like this private zone can be called a ‘water island’, by analogy with the ideas of Brusseau, who aspired to create resilient and biodiverse inner areas at block level. After all, 70% of the space in the city is private. It is therefore essential that private actors are also actively involved in an integrated water policy. It is a challenging task to get so many different individuals to agree on their ownership and privacy.

A possible strategy is to reuse water as a natural boundary and to gradually replace the brick boundary walls with wadis. In this way, an oasis can gradually emerge between two like-minded neighbours who exchange their hard boundary for a moat or wadi as a distance buffer. Ideally, a wadi should be created for an entire building block and serve not only as a physical buffer, but also as a rainwater buffer to further relieve the sewers. In this way, inspiring water gardens can be created.

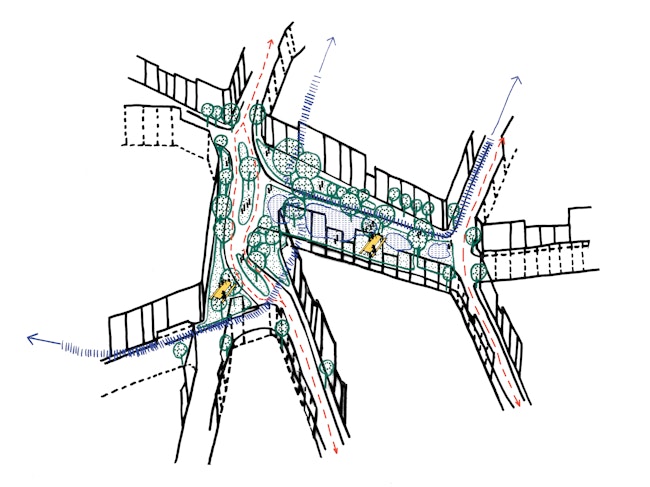

2 - Groeningerplein

The counterpart of the private inner area is the public square. Today, the previously unknown and unloved Groeningerplein suffers from congestion, but is nevertheless eagerly visited by local residents. Children come here to play and cycle, some let their dogs out for a short walk. Older people in particular look for a place to rest and look around and gather at the benches with the best view or under the shade of a few trees. The area is mainly paved, whereas in the past the Potvlier river flowed here naturally and later even dipped into the intriguing water figure of the 'Smousenhof'. It grew from a neighbourhood to a spacious court whose exact function is unknown.

Given its high degree of densification, Borgerhout has a great need for open spaces like this. What if we used water here as a driver to turn the Groeningerplein into a high-quality meeting place? Making water visible and tangible can be used as a mobility strategy to keep cars off the square, while young and old can cool off and settle down on the 'Potvliet' square.

3 - Cohousing project Kerkstraat: ‘Chapel’

As in the first case, the drained watercourse takes up space - which you can tell by the sagging floors in the old monastery. Soon, the construction of a co-housing project called 'Chapel' will start here and the garden will be shared among the local residents. The semi-private location requires a functional water point where water can be obtained for the maintenance of the gardens. But what if this becomes more than a hidden reservoir with an invisible service tap somewhere on an outside wall? By cutting out a strategic location on the site and integrating a contemporary water pump into the garden design, we can create a place for the residents to meet informally at ‘the well'.

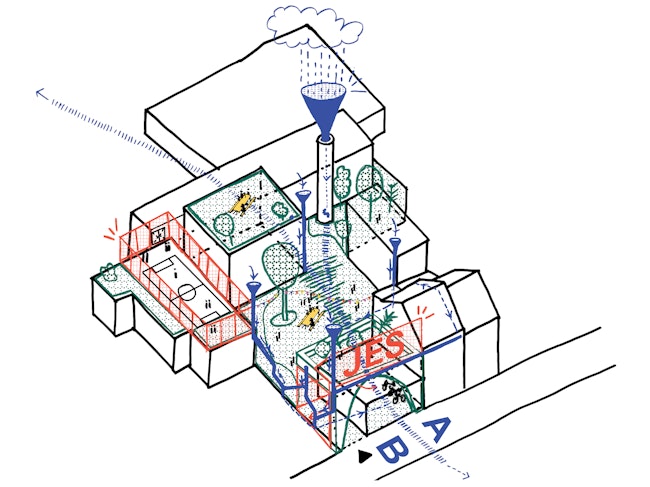

4 - JES: Jongeren en Stad, Borgerhout

Finally, we delve deeper into the site of the JES youth organisation, which, with its extensive programme, is keen to involve parents and local residents, turning its location into a semi-public extension of the neighbourhood. Their location in the old coffee roasting house, with the authentic tower next to the stream, makes them dream of a 'pond' for play and fun in the courtyard. Today, this only is one paved area with no greenery or blue.

After an initial consultation with some of the stakeholders in the neighbourhood (Klimplant, Curieus, Commons Lab, Groene Delta, Atelier Recup), we decided to start by talking with the young people themselves. Via a historical walk through the neighbourhood, the youngsters come into contact with the old route of the Potvliet. The confrontation with the missing blue is significant, but it brings about a lot of wild fantasies for a water story on their own terrain. At present, this team and our design partners are still busy drawing and thinking things through.

Each site requires a different methodology depending on the actors involved. Ideally, the result for various needs should be answered with the same, recognisable design language. In this way, the contemporary urban watercourse draws a recognisable line through a part of the city, to which people easily gravitate thanks to its readable status. The track could start at the old source near the Bleekhof and lead to the green Schijnvallei. The whole process of neighbourhood involvement, from learning about the past to the present, thinking about it together to building it, brings with it a boost in awareness of water and solidarity. The local residents will appropriate the new water spaces and share the principles of climate-proofing the use of water.

Today's urban brook brings with it a stream of water-filled meeting places where social cohesion is stimulated, while the urban heat effect is reduced and sewers and rivers are increasingly relieved by giving water a new and integrated place in the streetscape.